To go directly to Pre-Muscle Car Era Engines, click here, 1946 through 1963 Engine Development by Automaker.

We’re going to parse the U.S. automotive history prior to the muscle car era into three different sections: (1) Through WWII, (2) 1946 – 1954, and (3) 1955 – 1963. The last section details engines from the era 1946 through 1963.

- From the inception through WWII (1945). We won’t cover this time period in minute detail, instead touching on some of the some of the more significant events during this period. Although our focus will be on performance vehicles, we’ll also look at the larger overall automotive market. Performance cars were a smaller portion of this market and were hugely influenced by it.

- Post WWII, 1946 through 1954. These nine years saw stunning changes in the U.S. automotive market, with the growth of high-cost, large, powerful cars.

- 1955 through 1963. This was the pre-muscle car performance era, with large displacements, multi-carburetion and with engine outputs rivaling those of the muscle car era itself, which started in 1964 and extended through 1974.

- 1946 through 1963 Engine Development by Automaker. Information on each engine of the era, by automaker.

We are not going to spend much time on the automakers that didn’t last long enough to participate in the muscle car era, even though some of them were significant and were extremely interesting. Perhaps later we will be able to come back and fill in these stories.

1860’s Through WWII

The early domestic automotive scene was like the wild West. There was virtually no standardization and people entering the business had incredibly diverse backgrounds, some providing valuable skills and others not so much.

As the graph below shows, 1900 saw an explosion of activity in the automotive field, but there were handfuls of people working on ‘horseless carriages’ in the four previous decades. What was missing was the technology needed to first, produce a truly viable vehicle, and second, to produce it in volume sufficient to enable a company to survive.

The majority of automobiles produced prior to 1900 were far more similar to carriages than they were to, say, an early Ford. That shouldn’t be too surprising. What might be, though, is that the choice of propulsion was anything but standardized. There were cars powered by gas, oil, wood, coal, electricity, compressed air and clock springs. If any power source had the early edge, it would be electricity.

Electricity Rocks!

This might seem odd, given the range limitations imposed by batteries, especially early batteries. The fact that early cars tended to be lightweight helped the range, but in general, range wasn’t much of an issue at this time. The reason for this was the way people traveled then was much different than today and their expectations were vastly different. Travel between towns would continue to be largely by train, with cars being used for in-town travel. Roads at this time were mostly dirt, and the concept of ‘road maintenance’ didn’t even exist. This would change, of course, as people would increasingly use their cars for their travel needs, even between towns. By this time gasoline had taken the lead, aided by the ever-increasing number of filling stations. Although a few automakers had grandiose plans for stations dispensing compressed air or electricity to recharge vehicles so powered, these never came to fruition.

The Model T

Henry Ford’s Model T was introduced in 1908, which put the automobile within reach of the average person. It wasn’t the first car, just the first affordable car. As Ford refined manufacturing techniques and became more efficient, car prices fell year after year. It wasn’t long before a number of companies were offering aftermarket parts to allow the T to go faster. Of course, this was a time when Ford and their Model T dominated the market. For example, 1915 saw approximately 800,000 cars sold by the eight largest automakers. Of these, over 500,000 were Fords!

I know it seems strange now, but multi-valves and overhead cams go way back to the early part of the 20th Century. It would be another seven decades or so before this engine architecture became mainstream. The same could be said for turbocharging, fuel injection, direct fuel injection, and other technologies.

The automobile was still rather new when the first speed equipment made the scene. For the Ford Model T there was a rather sophisticated aftermarket, offering a surprisingly broad array of serious speed equipment. We’re talking things like overhead valve heads, with overhead cams and four valves per cylinder! Even when the muscle car was in its heyday, you could only dream about stuff like this! Speedway Engineering Equipment of Indianapolis offered Craig-Hunt 16-valve heads, as well as performance cranks, connecting rods, pistons and rings, oiling systems and a bunch more. Chevrolet Brothers Manufacturing company offered Frontenac 16-valve racing heads.

Model T Price Plummets

Model T price dropped by more than two-thirds over the length of its production, due to manufacturing efficiencies and economies of scale. This phenomenon was certainly seen first and foremost with Ford and the ‘T’, but this reduction in cost over time was seen in many industries such as radios, televisions and personal computers.

This chart shows how the price of the Model T declined over time, as manufacturing efficiency increased. These values are for the five-passenger touring car, but other body styles showed similar declines.

In the interest of addressing a misconception, Henry Ford did not invent the assembly line. The innovation he was responsible for was the moving assembly line. Introduced in late 1913, the moving assembly line was instrumental in reducing the time to make a Ford from twelve hours to roughly one and one-half hours.

People discovered how fun and exciting it can be to go fast(er) almost as early as automobiles themselves were invented! The mainstream auto manufacturers in the early years weren’t really interested in this market segment, although there were some smaller automakers who did somewhat specialize in performance models. This wouldn’t change until mainly the ’50’s, when a majority of U.S. auto makers started offering larger, more powerful engines in their larger cars.

The Common View. . .

Most of us tend to view our automotive high-performance history in something of a linear way. First came small, crude, low compression engines that eked out two-digit horsepower figures. These were inline, valve-in-block designs, limited to lower rpms. Later came bigger engines, some in V8, V12 and V16 configurations, higher compression ratios, more sophisticated brakes and transmissions, etc.

According to this narration, things got interesting in the ‘50’s, with increasing engine displacements, multi-carburetion, higher compression ratios and much higher horsepower. This era even saw fuel injected V8s.

Performance exploded in the ‘60’s with the birth of the muscle car, with a return to mediocre performance in the 1970’s. We had to wait until the ‘80’s and later to see the widespread use of fuel injection, aluminum alloy heads with overhead cams and four-valves-per-cylinder. The ‘90’s and 2000’s witnessed flex fuel engines, variable valve timing and direct fuel injection. While there is some truth in this, the path that engine technology took is not a straight one. The common view was certainly not accurate!

Over a Thousand Companies!

Over the past one hundred twenty plus years, there have been literally hundreds of U.S. automakers who have come and gone. The total number is probably in excess of one thousand! As with any new product, the ambitious flocked to get involved and become automakers themselves, sensing (rightly) that there were fortunes to be made. Of course, some did make fortunes (Ford, Chrysler, Durant, etc.), but for many it was a short-lived venture. In the first twenty years of the new century, untold numbers of “automakers” came and went. Some had managed to design and produce products and offer them for sale, many had not. Some had sales figures in the hundreds before losing the battle, and for others the number was in the single digits. All sorts of backgrounds were represented in those who entered the business, blacksmiths, bicycle makers, general mechanics, hobbyists, and businessmen with little if any knowledge of automobiles.

Take a look at the following graph, which shows the numbers of automakers entering and exiting the automobile manufacturing business by year. Between 1900 and 1920, there were literally dozens of automotive startups every year, and an equal number of companies closing shop! These cars were powered by gasoline, kerosene, steam, electricity, compressed air, and even one with a windup clock spring. At least one was a gas/electric “hybrid”!

In the 1890’s, electric cars greatly outnumbered gas! Both Oldsmobile and Studebaker originally started with electric vehicles. One source states that Ford’s moving assembly line and the efficiencies it offered were the final nail in the coffin of electric vehicles. Once the momentum swung to gas engines, that particular battle was over.

It’s not clear why 1914 shows such huge numbers. WWI started in July of that year, but the US was not yet involved.

A Porsche But Not a Porsche

The Austrian Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, at age 23, built his first car, the Lohner Electric Chaise. It was the world’s first front-wheel-drive. Porsche’s second car was a hybrid, using an internal combustion engine to spin a generator that provided power to electric motors located in the wheel hubs. On battery alone, the car could travel nearly 40 miles. This was circa 1898. And, yes, it’s that Ferdinand Porsche! I knew that Porsche was a favorite of Adolph Hitler and that he designed a diesel electric heavy tank during WWII. Of course, all modern locomotives for the past seventy years have been diesel electric. Anyway, the tank broke down and caught fire when it was being demonstrated to Der Fuhrer! Too bad Hitler couldn’t have been a passenger at that particular time.

Gone but not Forgotten

I think it’s fascinating to read about long-gone automakers and to see, or see pictures of, their vehicles. These were “living, breathing” companies, with from two to ten thousand (or more) people involved, living and working in their communities, supporting their families.

Their vehicles themselves often reflect individual thought and innovation, as common practices had often yet to develop. It’s easy to think “out of the box”, when there is no box! I encourage you to avail yourself of the books and web resources that deal with these companies and their vehicles. If you happen to be a US history buff, it’s really cool to see how the particular product, cars, “fits in” with the overall era.

This doesn’t include the small, “here today, gone tomorrow” companies for which little information exists. Things were already slowing down by the time the Great Depression hit (1929), which would be considered the normal industry consolidation. After all, some fifty-plus companies opening and closing every year wasn’t going to go on forever! In addition to the Depression, the war years (’42 – ’45), when most automakers were involved in the war effort, saw very few entrances to or exits from the business.

Not a Unique Process

In many ways the evolution of the auto industry was mirrored in the evolution of other industries. For an example, look at the PC industry. At one time there were dozens and dozens of American PC makers, with names like Commodore, Atari, Sinclair, Texas Instruments, Packard Bell, Edge, Gateway, Osborne, Zenith, NeXT and Tandem, to name but a few. Anyone who could even assemble a computer (Michael Dell) was making money hand over fist.

However, today if you stroll (or saunter, sashay, or whatever it is you do…) down the PC aisle of your local office supplies mega-store, you will see a mere handful of PC maker’s products. The industry consolidated into a relative few large companies. The auto industry did the same thing, as did the aircraft, radio, television, motorcycle, and banking industries, as well as many others. It’s inevitable and inescapable. People flock to the “new industry” and the resulting competition spurs development and invention, as well as creating a few winners and a lot of losers.

First Generation Engine and Car Technology

Yeah, maybe the designation ‘First Generation’ is a bit arbitrary, but I’m gonna run with it. Really, what better car and engine to focus on as premier examples of early automotive state-of-the-art than the Model T and its 175.6 cubic inch straight four? The Model T was the standard bearer in so many ways; reliability, longevity and brilliant engineering, to name three.

The exhaust manifold was located above the intake manifold on this engine. Note the low-mounted carburetor. Remember that there was no fuel pump, the gasoline being gravity fed. Gotta have your tank above the carb!

Introduced in 1909, the 175.6 in3 straight four had a 3.74 in. bore and a 3.98 in. stroke. The 20hp was all in by 1,800 rpm. The 3.98:1 compression ratio allowed not only problem-free operation on the low octane gasoline at the time, but it could also use kerosene or grain alcohol. E85 had nothing on this engine! Note that the exhaust manifold, fed by all four exhaust ports, is mounted above the intake manifold. The intake feeds two intake ports, each of which feeds two cylinders.

The engine initially used a water pump, but that was dispensed with in favor of a system that simply used coolant temperature differential to circulate the liquid. A magneto was used to generate the electrical energy used for the ignition. No battery was needed; there was no starter, the engine being hand-crank only, and the lights were not electric.

Non-Electric Headlights?

Well, yes. In the earliest part of the 20th century the majority of homes and offices with lighting did not have electric lights; they used gas. Early car headlights were often powered by acetylene gas.

If you put calcium carbide in a container with water, acetylene gas was produced. Miners used the same method for their hardhat-mounted lights.

This is a diagram of an acetylene gas generator. These were often referred to as ‘carbide lamps’.

Some Unusual Features

The single barrel carburetor was the model of simplicity, with nothing so fancy as an accelerator pump. Both the throttle and the spark advance were controlled by hand levers. The Model T utilized transverse leaf springs front and rear. Wait—didn’t the C4 Corvette have a rear transverse leaf? Why, yes it did; made of fiberglass. Since a transverse leaf can’t locate the rear axle, the T used a torque tube to do so. This, of course, enclosed the driveshaft. The rear suspension was of a type known as de Deon, which used a tube to tie the two rear hubs together, in a quasi-independent type of rear suspension. The suspension allowed high ground clearance, which was significant given some of the road conditions encountered.

Yeah, I knew that you were thinking “de Deon? Just what the …?”. So, I thought I’d show you what this looked like. If you look at early photos of cars on roads, some of them show the incredible axle-deep mud that cars had to deal with. Most roads were not even gravel covered at this time, and the ground clearance of the T could be of incalculable value.

I grabbed this from the US Census Bureau. They haven’t done a damn thing for me, so I thought they could at least donate this pic.

Two-Speed Transmission

The two-speed manual transmission used a planetary gearset; these would become common in another four decades or so, when fully automatic transmissions became commonplace. Surprisingly, planetary gearsets were fairly common in manual transmissions at this time.

The cylinder head had huge combustion chambers, but this was typical with the low compression ratios of the era. Spark plugs were positioned closer to the valves than the main part of the combustion chamber.

Internal Components

Connecting rods were long and thin; plenty strong for 20hp! Note how the small end was fastened.

Pistons were cast iron initially and had four rings. How to Hop Up Ford & Mercury V8 Engines, by Roger Huntington, copyright 1951 by Floyd Clymer, indicates that this is mainly for stability of the pistons, to keep them from scraping their sides on the cylinder walls. In fact, this publication specifically stated that 3-ring ‘racing pistons’ were unacceptable for street use specifically for this reason! Later pistons were of aluminum.

Those Iron Pistons

Yes, most early pistons were made of iron or steel. This makes perfect sense, given the low engine speeds and the challenges aluminum pistons presented when they became common. There were, in fact, aluminum pistons used in some engines in the earliest part of the automobile era; they just weren’t common.

The expansion rate of aluminum pistons presented challenges, and the earlier aluminum pistons in general use contained steel struts to control the thermal expansion. The earlier aluminum pistons were quite fragile and dropping one from bench height onto a hard floor would most likely result in cracking. Aluminum, though known indirectly in antiquity, is remarkably difficult to produce from its natural state as bauxite, which is the primary source of aluminum. Aluminum has a remarkable affinity for oxygen and does not exist in nature by itself. The ancient Greeks used alum (KAl(SO4)2·12H2O) to fix dye to fabric. It wasn’t until 1825 that the element was produced in its pure form. In 1954 aluminum became the most produced non-ferrous metal. wikipedia.org/wiki/Aluminium

The crankshaft was simple yet functional. Again, plenty strong enough. Three main bearings were used and were of the poured babbitt type. (See Engine Lubrication and Bearings) Three main bearings rather than the five you’d see in a four-banger today.

This is a Holley NH carburetor for the ‘T’. As with the other Model T engine components, is is a model of simplicity.

The T intake (below) and exhaust (above) manifolds were remarkably simple and functional. Air flow wasn’t much of a concern when you’re making 20hp!

Here’s a Champion sparkplug advertisement from the June 17, 1919 ‘The Buffalo News.’ The Ford ‘T’ used Champion plugs. AC Sparkplugs had a similar ad, with a lengthy list of the companies who used their products. This is a reflection of just how many automakers there were at this time. There were over four dozen passenger car companies listed!

I thought it would be a shame to end this section without showing the total package, a Ford Model T in all its magnificence. The runabout was just one of six or so Model T styles available in 1927.

The 1930’s

The 1930’s saw all aspects of American life impacted by the Great Depression, and the auto industry was no exception. However, this decade did see such things as larger engines in straight and vee configurations. Automatic transmissions became available, as did four-wheel hydraulic brakes, heaters, radios and low-pressure balloon tires for improved ride quality. Also, of note are the streamlined bodies that appeared during this decade. Styling became all important in the ‘30’s, with innovation becoming merely incremental. Most of the major features a 1950’s car offered were already existing, though not necessarily commonplace.

As you might expect, the Depression was hard on most US auto makers and cost some of them their very existence. Examples include Auburn (1900 – ’36), Brewster (’15 – ’37), Cord (’29 – ’37), Cunningham (’07 – ’36), Detroit Electric (’07 – ’39), Duesenberg (’20 – ’37), Essex (’19 – ’32), Franklin (’02 – ’34), Marmon (’02 – ’33), Overland ’03 – ’39), Peerless (’00 – ’33), Stutz (’11 – ’35) and Willys-Knight (’14 – ’33). There were others, but these are the most noteworthy.

The comings and goings of automobile companies would continue to the present day, though at a reduced pace. Some recent (ish) examples:

- Willys-Overland 1953

- Nash 1957

- Packard 1958

- Studebaker 1963

- Rambler 1969

- King Midget 1970

- Int. Harvester 1980

- AMC 1987

- Plymouth 2001

- Oldsmobile 2004

- Avanti 2007

- Saturn 2010

- Pontiac 2010

- Mercury 2011

- ??

(Data source: wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_defunct_automobile_manufacturers_of_the_United_States)

There were some performance cars in the 1930’s. These had up to 200hp, while hauling around sometimes over 5,000 pounds, and costing up to around $5,500 (about $100,000 in 2019). Most of the auto makers that would survive and participate in the muscle car era had relatively meager performance offerings during the ’30’s.

High-Performance Cars

Below are some of the noteworthy high-performance offerings from the 1930’s.

Affordable Performance

Be aware that these tables contain generalized information. For example, the Buick 320cid inline 8 engine was introduced in 1936 at 120hp, saw 130hp in ’37 and reached 141hp in ’38 and ’39. This engine persisted until 1952, making 170 hp. Also, note the under-square nature (stroke much longer than bore) of the majority of these engines, which reflected the prevalent engine practice of the time. These were not high RPM engines!

The Problem with 8’s

A straight eight, even if it has overhead valves, is inherently very, very limited. It can’t do high rpms, and the rotating mass is, well, massive! This engine configuration came about as a response to those buyers who wanted more power than a six-cylinder engine would give them, but who couldn’t step up to a V8. Remember, Ford had an affordable V8, which was a valve-in-block design. This engine was revolutionary and was offered from 1932 until 1953. But what if you wanted a Chrysler or GM product? Or one of the independents? They chose to serve this niche with a more tried and proven approach, the straight eight.

The enormously long crankshaft of a straight eight prohibited high engine speeds. The crankshaft simply didn’t have high torsional rigidity, given its length. That was fine, as engines at that time didn’t flow well enough to support high rpm power production anyway. Of course, the long engine made for challenges in packaging, requiring a long hood.

Gotta Reseal My Top Today!

This is an illustration of an advancement that took place in the mid ‘30’s. In 1935 GM introduced their models with ‘turret tops’. These were all-steel tops, the type of which we’re all familiar and have likely never thought twice about. However, things were not always this way. Prior to the innovation of the turret top, car tops were not steel, they were a combination of canvas and wood, which required regular resealing.

But why the heck weren’t they solid steel, like they’ve been for the past eight decades? As it turns out, the size of available hot-rolled steel had been a limiting factor. Plus, cars had not yet begun the trend toward lowered bodies, and people couldn’t even see the tops of cars. The recent availability of 76” hot-rolled steel allowed this innovation. The resulting bodies were stiffer and stronger, as well as more attractive and maintenance-free. Soon the entire industry would follow suit.

These weren’t the first all-steel tops, but this was when they became the norm rather than the exception. Perhaps it would be fair to say that it was this time that the last vestige of carriages (as in horses…) still present in auto design went away.

The Pontiac ‘Silver Streak’ is just one example of an engine that spanned from the pre-war era, well into the post-war era (1933 – 1954). It arguably had more in common with the pre-WWI Ford 4 than it did with engines that were appearing in the early- and mid-Fifties.

The First Performance Engine for the Common Man

The Ford Flathead V8

This was perhaps the most significant engine of the 20th Century. It is the ancestor of all of the muscle car era engines as well as the V8 engines in use today. Why? Simply because it was the engine that brought V8 power within reach of most of us, the average buyers.

Yes, there had been V8 engines in use, here and there, for thirty years prior to Ford’s introduction of their new flathead, 221cid V8 in 1932. In fact, Ford’s Lincoln Motor Car division had been manufacturing V8 engines for some time. Ford purchased Lincoln from its founder, Henry Leland, in 1922, just five years after being founded by Leland. Leland was also one of the founders of Cadillac.

Early V8

At the time of the Ford acquisition of Lincoln, the Lincoln V8 was a 60° L-Head unit of 357.8 cubic inches displacement. It made all of 81hp at 2,600 rpm, using a 4.8:1 compression ratio. As was the norm at this time, this was an expensive engine to manufacture and was available only in expensive automobiles. The same was true with other automakers and their V-configuration engines, whether 8, 12 or 16 cylinders. The average buyer was just never going to afford a V8 powered car, period.

Henry Ford changed this with his new V8 in 1932. What made this engine revolutionary was that it was designed with a single-piece block, something not previously thought possible. Virtually all V-configuration blocks had been assembled from multiple castings.

Here’s a picture of a Lincoln V8, that shows where two of the three block components meet. Casting a block in smaller pieces like this was far less challenging than trying to cast them as one piece. As you might imagine, the extra casting steps and machining of additional mating surfaces made this design labor intensive and expensive.

A True Skunkworks Project

Ford worked in relative secrecy, involving only those who needed to know. He closed the majority of the Ford factories, being less than forthcoming about the details, and apparently saying only that they would reopen when the next generation of Ford cars were ready for production. Twenty-four of the thirty-one plants were shut down, with only nine of those twenty-four ever reopening. This was due to the economic ruin wrought by the Great Depression of 1929 – 1939.

A handful of Ford engineers were assigned the task of developing the one-piece 90° iron engine block. The project was exceedingly challenging. And why wouldn’t it be? This had never been done, right?

Well, that’s not entirely correct. Just a couple of years earlier, both the low-volume Viking and Oakland, both belonging to GM, had produced relatively small numbers of mono-block V8 engines. The all-important distinction, though, is that Ford found a way to produce these engines in far larger quantities, and at a cost that made the engines cheap enough to manufacture to be able to offer them in midrange models. This might be a bit like the incandescent light bulb. Thomas Edison didn’t conceive it or invent it, he perfected it. And the rest is history!

Flathead Engine Construction

Early V-type automotive engines used blade-fork connecting rods, as did V-type aircraft engines and motorcycle engines. The Ford V8 abandoned this practice in lieu of the side-by-side mounting of rods on a single crank journal that’s in use today.

T-Head and L-Head

The flathead used a T-head design, rather than an L-head. This required the exhaust ports to be routed between the cylinders, to the exhaust side of the engine. This sometimes taxed an already marginal cooling system.

An L-head engine has the valves positioned such that the intake valve is on the intake side of the engine and the exhaust valve on the exhaust side. This allows for more straightforward routing of ports. It does place the ports between the cylinders, though.

A T-head layout has both valves on the inside, intake, side of the engine. This removes them from between the cylinders but puts the exhaust valves on the ‘wrong’ side of the cylinder bank, requiring exhaust ports be routed between cylinders.

The two inner cylinders of each bank routed their exhaust between them, resulting in three, not four, exhaust ports to the exhaust manifold. To the unsuspecting, this made for an odd look.

This shows the flathead block and the direction of exhaust flow through the block.

Unusual Crankshaft

The flathead continued to use the pre-existing three main journals for the crankshaft, rather than the five that would become common later. This, as I understand it, was done strictly to control costs.

The flathead crankshaft was a high strength cast 90° piece with three main bearings. Flat (180°) cranks were commonly used in earlier V8 engines, as they were easier to manufacture. Ford was able to produce this piece economically enough to keep engine manufacturing costs low. Another innovation.

The flathead pistons weren’t all that different from pistons of contemporary engines. Note the fourth, lower, ring.

Pistons were originally made of cast iron. 1935 saw the first use of aluminum pistons in the flathead.

The Ford flathead V8 wasn’t without its early problems, which included excessive oil consumption, cracked pistons and overheating. Ford worked aggressively to address these issues. It’s said that Ford also was very responsive in addressing the needs of customers who had already purchased a V8 car and were experiencing problems.

Other flathead changes addressed the desire for higher output. The 65hp engine had its compression ratio raised from 5.5:1 to 6.33:1, adding 10hp. The 1bbl Detroit Lubricator carburetor was replaced by a Stromberg 2bbl unit, adding another 10hp for a total of 85.

Improvements

1936 saw the use of insert main bearings, replacing the poured babbitt. In 1937 a smaller 136cid V8 became available. The two engines were named V-8/85 and V-8/60 to differentiate them. The water pump was relocated and was modified to be lubricated with oil rather than grease. The fan was modified to incorporate six blades. New heads featured centered coolant outlets and combustion chambers were modified to allow the use of domed pistons. The compression ratio fell slightly to 6.12:1. A less obvious change was the move to a new ‘LB’ block that featured larger main bearing journals.

In 1939 Mercury got a new version of the engine that had a 3 3/16” bore, 1/8” larger than the Ford V-8/85. This bumped the displacement to 239cid and produced 95hp. In 1941 compression ratios for both engines were increased, which resulted in a Ford rating of 95hp and Mercury an even 100hp.

Connecting rods were rather contemporary looking. They no longer had the funky rotated cap that the Model T engine had.

Model T Information

There are many vintage and contemporary books about the Ford flathead V8 that will tell you everything you need to know to increase durability or output, or both. I found a 1951 copy of How to Hop Up Ford and Mercury V8 Engines by Roger Huntington for about 5 bucks in a used bookstore. In addition, I think there are more aftermarket parts made for the engine than ever before. Thirty or more years ago, the process of going through your flathead engine would have involved making many phone calls and ordering whatever catalogs you could find. It could take months of work to find some parts. Today it’s mostly a matter of just getting online!

A thing of beauty it was! Here, some seven decades after the flathead was replaced by the M-E-L Y-block engine family, many people still regard the flathead as a work of art.

Why not an OHV?

It’s a fair question to ask why Henry Ford didn’t make his new V8 an overhead valve design. After all, OHV designs had been around for ages even at this time. They weren’t yet popular probably due to higher manufacturing costs and a lack of perceived value by the public.

Going beyond OHV designs, there had been at this time more than a few overhead cam head designs! In fact, Henry Ford himself had patented one such design in the early ’30’s.

This image is from the USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office) and is a portion of Ford’s patent for an overhead camshaft engine.

Ford was very aware of the options for his new engine and must have carefully weighed the various elements when deciding on valve/cam designs. These would be such variables as tooling costs, manufacturing costs, material costs and market acceptance. I don’t know for sure, but it seems that ‘going too far’ might have carried the risk of the buying public not understanding the benefits of an OHV or OHC design. We Americans have turned up our noses at something new more than once in the past, not stopping to consider the potential benefits.

Perhaps buried in writings by and about Henry Ford are clues to his thoughts at this time. Regardless, his V8 flathead was met with wild market acceptance and will forever be regarded as one of the landmark and historic internal combustion engines. This engine whet the appetite of Americans for V8 performance, laying the foundation for the myriad V8 engines that would emerge post WWII, after domestic automakers got their feet back under themselves. Thanks, Henry!

Buyers Loved the Flathead!

This is one rare letter from an appreciative customer! Not ‘customer’, really, as much as maybe ‘user’. I mean, what do you call someone who really appreciated your products, but stole them rather than buy them? The author, of course, is one Clyde Barrow who was one half of the infamous Bonnie and Clyde. Maybe Clyde wasn’t all bad, since he did take the time to write this letter of appreciation to Henry Ford. Well, maybe that’s being a little too kind.

Behold the 1934 Ford Deluxe that was the last set of wheels for Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. Clyde carried a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) which usually allowed him to outgun his pursuers. However, on May 23rd, 1934, the posse waiting in ambush also possessed similar weapons. The result is what you see here.

Clyde himself didn’t enrich the Ford Motor Company directly, since he stole the cars he drove. Come to think of it, though, I guess his theft victims did have to replace those cars.

World War II

The 1930’s rolled into the 1940’s with no huge changes in the auto industry. After the US was attacked by Japan in December of 1941, the government turned most of industry (and all of the auto industry) to the production of the machines and materiel of war. This was something that our enemies hugely underestimated.

The period was interspersed with other flathead modifications, such as the change from 21 head bolts to 24, the move to a fully counterbalanced crankshaft, and the change to a different Stromberg carb and finally a Holley. Remember that Holley was very much a mainstream carburetor maker, like Carter, Stromberg, Rochester and so many others. It would still be some years before Holley started focusing on performance 4bbl carbs. In fact, by this time Ford had been using Holley carburetors for over three decades.

US Automaker WW2 Production

Ford built over 86,000 aircraft, a large portion of them B24 Liberator heavy bombers. They also built over 277,000 jeeps. GM’s Fisher Body made over 11,000 Sherman tanks; Buick made over 2,500 M-18 “Hellcat” tank destroyers; Cadillac made M-5 tanks; Pontiac made axles, torpedoes and anti-aircraft guns; Oldsmobile made millions of tons of artillery shells and Chevy made over 280,000 trucks. Chrysler built M3 and Sherman tanks. (Chrysler Defense builds the M1 Abrams main battle tank, America’s front-line tank.) Both Pontiac and American Harvester built the Mark 14 torpedo.

These figures represent just a portion of the output of the companies mentioned, and there were many other companies involved in the war effort.

Chrysler Materiel

Chrysler was greatly involved in the war effort and they put their expertise to good use. They designed and built a thirty-cylinder gas engine that powered the M4A4 version of the Sherman medium tank. The engine demonstrated Chrysler’s ingenuity, by using five six-cylinder engines to make a 30-cylinder engine. This tank was manufactured by a number of companies in absolutely astounding numbers. What it made up for in capabilities it would (attempt to) make up in numbers.

This table shows just a small sample of the wartime production by U.S. automakers. There were more aircraft subassemblies produced by automakers than by aircraft manufacturers. The U.S. and its allies dramatically outproduced the axis countries in war materiel by a factor of several to one.

M4 Sherman Tank

The M4 “Sherman” medium tank was named after Civil war general William Tecumseh Sherman. It was to be, unfortunately, a costly learning lesson for the US army.

The tank was too small to effectively battle German panzers. Its armor was too thin and its 75mm gun was not powerful enough. Their 75mm shells were known to bounce off of German Tiger frontal armor, where the German 88mm gun would shoot right through a Sherman. There were times when three or four M4s were taken out by a Tiger, before a surviving M4 could maneuver to a position where it could, at close range, take a shot at the rear of the Tiger, where armor was thinner.

It’s been said that US tank crews universally hated the tanks, which they regarded as death traps. They would often affix logs or other materials to the outside in an effort to add further protection. As limited in ability as it was, US soldiers did what they do and made the best of it. The lesson was learned, though, and the current US main battle tank, the M1A2 Abrams, is widely regarded as the most capable in the world.

This tank was named after Civil War Union general William Tecumseh Sherman. His middle name was due to his father’s fascination with the Shawnee chief of the same name.

Here’s a B-24 Liberator, very possibly made by Ford. The B-24 was a workhorse in Europe, though it never gained the reputation that Boeing’s B-17 did. James Stuart (It’s a Wonderful Life) piloted 20 missions in B-24’s and possibly as many as 20 more uncredited missions.

War Rationing

In the U.S. rationing started in the spring of 1942, with sugar first and then coffee. The rationing of some things, like gasoline, made obvious sense in wartime. But sugar and coffee? The Philippines fell to the Japanese, and we lost a major source of sugar. Ships that would normally be shipping sugar and coffee to the USA were far more needed to ship war supplies overseas. Other items rationed were rubber, nylon, silk, meat, lard, oils and shortening, butter, margarine, cheese, as well as other items and foodstuffs. Rationing ended in the US in 1946. In Britain, rationing of some items lasted until 1954!

Chrysler Experimentation

Sometime in the mid to late ‘30’s Chrysler tasked its engineers with identifying the best engine head configuration. Going through an exhaustive process of testing, they concluded that the hemispherical head design was overall optimal for the desired characteristics as defined at that time. This set the stage for Chrysler’s 2220 engine, which was a hemispherical head, inverted V16, 36.4-liter, liquid cooled engine proposed for the still experimental aircraft that would become the P-47 Thunderbolt. The engine made some 2,500hp, and although not used by the P-47, it was Chrysler’s first hemi head engine. This experience would serve them well when the post-war automakers were finally able to introduce new engine designs in the very late ‘40’s and early ‘50’s.

Thunderbolt was a monster of an aircraft. It escorted US bombers to Germany and back and was death to anything on the ground. The A10 ‘Warthog’ is actually named ‘Thunderbolt II’.

The Daimler-Benz DB 605 engine that powered the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter during WW2 had its roots in the 1930’s. There was a lot of aircraft engine technology that eventually made it to the automotive field. This engine is fascinating in its use of technology and very well illustrates the state of the art in engine design at this time.

Daimler-Benz DB 605

Yeah, this site is about American cars and engines, and I picked a German engine to feature, and an airplane engine to boot! There were some very impressive U.S. and British engines, but the sheer buttload of forward thinking in this engine and plane have always captivated me.

This plane had its roots firmly planted in the pre-war 1930’s, yet with updating, it remained competitive throughout the war. And that’s with the allies fielding all-new planes, like the Spitfire and the P-51 Mustang.

The DB 605 was a 35.7-liter, liquid cooled, inverted V12. Maximum engine speed was 2,800 rpm, where it made over 1,400 hp. The supercharger had a barometrically controlled hydraulic clutch to automatically adjust for altitude. The engine had overhead cams and was direct fuel injected! In addition, it had water/methanol injection for “emergency power”.

Don’t miss the fact that this engine was inverted! The oil would indeed tend to flow down into the bottom of the pistons, where it would be tossed back up to coat the cylinder walls. The inversion of an engine is incredibly unusual, to say the least, and presents numerous technical challenges. There must be at least one significant benefit to justify such an unusual configuration, right? Yes indeed, and that advantage is a lower positioning in the fuselage and a lowered center of gravity. Seemingly no other aircraft designer deemed this lowered center of gravity a significant enough factor to undergo the challenge of designing a similar engine. Remember that such a configuration requires fuel injection, which itself was not yet popular.

Could this technology have been applied to car engines sooner? Absolutely! After all, it would be the mid ‘50’s before OHV engines became prevalent. What was missing was the all-important urgency, as well as resources. Creating machines of war, especially in time of war, isn’t at all about profit and loss. Creating autos is all about profit and loss. Still, the time spans from the inception of a technology to the widespread automotive adoption seem awfully long sometime, don’t they?

War-Era Ingenuity

World War I and World War II eras changed a lot of everyday things, particularly in some of the European countries. One interesting response to the scarcity of gasoline was the use of coal gas to power some vehicles.

Coal gas is produced from coal, obviously enough. It consists of approximately equal parts hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Before natural gas became readily available, coal gas was used for many of the same uses, including cooking and heating.

Coal gas was pressed into service to power vehicles. It wasn’t at that time possible to store it under any sort of real pressure, so it became common to use low pressure bags affixed to the vehicle top. As you might imagine, range was severely limited. I’m not sure about other countries, but Germany had distributed roadside ‘stations’ for the refueling of coal gas buses.

The Reawakening (1946 – 1954)

Prior to the muscle car era itself, the post-World War Two automotive market can be separated into two eras. The first era starts with 1946, the resumption of auto production after the automakers converted back to cars, having produced war materiel from ‘42 to ‘45. This era extended through 1954. There were so many significant advancements in 1955 that this is considered the beginning of the next era, the one that led directly to the muscle car era. As such, this era goes from 1955 through 1963.

Post-War Explosion

The end of World War II saw the resumption of car production by American car companies. The combination of the end of the Great Depression and the pent-up demand resulted in an explosion in US auto sales.

1941: 3,571,000

1942: 1,142,000 (early end)

… US in WWII …

1946: 2,226,000

1947: 3,361,000

1948: 3,414,000

1949: 5,241,000

1950: 6,350,000

Post war cars became larger, with smooth lines and streamlined styling that is still pleasing to the eye today. The first of millions of modern overhead valve V8 engines appeared at the end of the ‘40’s, with a tsunami of new OHV V8s appearing in the 1950’s.

This was truly the “Mother of all seller’s markets”. People tended to have money, since the war effort resulted in full employment and goods were limited during the war.

These nine years might have witnessed more changes in the U.S. automotive field than any other comparable time span.

What? I Can’t Have a Chevy?

Often times new car buyers were forced to accept their second, third or fourth choices, due to the limited supply of new cars. For most buyers, just having a new car was enough, even though it might not have been their make or model of choice. It would take some time for supply and demand to balance and for a normalcy to return to the auto market. Change would be minimal for the next few years, with 1949 and 1950 being years of huge change in the industry as market forces rekindled competition and automakers got a bit of breathing room. The decade of the fifties would witness absolutely breathtaking changes in every facet of the automobile market.

The 1946 cars were essentially “new” 1942 models. Average horsepower was a handful of hp over 100, with a horsepower per cubic inch (hp/in3) being a paltry 0.424. Average engine age was well over seven years and compression ratios averaged about 6.7:1.

My How Things Changed!

Contrast this with the end of the era, 1954. The most powerful ‘46 engine was Buick’s 320cid OHV inline 8, with 144hp. In 1954 the title went to Chrysler’s 331 hemi, with 235hp. 1946 saw only two OHV eight-cylinder engines, both Buick inlines. In ‘54, there were eight OHV V8s, including three hemi designs. Average horsepower rose from 106 to 147, a 39% increase.

Vehicle bodies also changed markedly during this period. The ‘46 models were characterized by 2-piece windshields of flat glass, mildly swept and tilted back. Both front and rear fenders were of the style that protruded from the body, and hoods were domed and anything but flat. Traces of running boards were still seen, as were several fastback models. Small rear windows were the norm, and just what the heck was a “hardtop”?

By the end of this era, front and rear fenders were nicely integrated into the bodies. Hoods and trunk decks were much flatter and some rear windows were huge. Front glass was well sloped back, curved, and wrapped around the front of the passenger compartment. Hardtop body styles abounded.

While in 1946 only Buick and Cadillac offered a true automatic transmission, 1954 saw every other automaker on board with an automatic. This by no means reflects all of the changes during this period.

A Whole Bunch of Firsts

The following table gives the dates that each automaker introduced basic features or reached engine benchmarks. These include:

- First overhead valve engine

- First V8 engine

- First OHV V8 engine

- All engines OHV

- Four-barrel carburetor

- First use of multi-carburetion (3 x 2bbl or 2 x 4bbl)

- Year that 200hp was reached

- Year that 300hp was reached

- One horsepower per cubic inch achieved (not all reached this)

- Use of semi-automatic transmission (Just Chrysler companies)

- Use of four speed manual transmission

- Fully automatic transmission

- Power steering introduced

- Power brakes introduced

- Air conditioning available

- 12V electrics used (from prior 6V)

You might notice the absence of companies like DeSoto, Packard, Studebaker and others. We’re just focusing on companies who made it through to the muscle car era, although at some later time we may fill in information on the other, now gone, automakers.

The engine story in 1946 saw one automaker, Buick, with two OHV eights. These were inline eights. There were V8 engines, but they weren’t overhead valve. Plus, there were inline L-head sixes and Chevy’s OHV six. Buick’s inline eight 322 OHV held the horsepower title, at a mere 144hp. Engines were split almost evenly between six cylinders and eight. In 1963, not only were all engines overhead valve, but V8s led sixes (inline and V) by a margin of almost five to one! Of course, the inline eights had been relegated to the trash heap of history. Most of the fours and sixes were inline configurations, but Buick did already have their beautiful little 198cid V6.

Why So Many V8 Engines?

To a great extent, the engine offerings reflected what the buying public wanted. None of the automakers in the early post-war years had an inkling of how popular V8 engines would become.

This engine demand caused varying degrees of difficulty for the automakers. Chevrolet borrowed the Pontiac-developed stud mounted, pressed steel rocker arm design. At this time, it was very rare indeed for one company to borrow technology from another, even if those two companies were under the same umbrella, such as G.M. To illustrate this point, three of the Chrysler companies had their own hemispherical and/or polyspherical head OHV V8 engine designs that shared nothing!

This last point became an issue for the Chrysler companies, as V8 demand grew. The hemi-head (small ‘h’) engines were expensive to manufacture. The head design was the result of exhaustive research the company had done, both before and during the war, as well as their design and manufacturing experience for wartime production. The number of V8 engine they sold, all hemi designs, put them at a substantial cost disadvantage relative to their competition, with their cheaper to manufacture wedge head designs.

What’s so special about V8’s?

The V8 was an infinitely better configuration than the straight eight. The packaging of the cylinders was more compact, and the cylinders not being oriented vertically allowed an engine compartment that was both not as long and not as tall as with a straight eight. Stylists didn’t have to design around the engine to such a great degree. The cylinders being closer together allowed a single carburetor to more efficiently feed equal quality mixture to all cylinders.

One advantage that would be huge when engines began to make power at higher and higher engine speeds is the V8 crankshaft. It’s much shorter and stouter than one for an inline, and much more resistant to twisting, with the resulting vibrations and potential problems. The main thing initially prohibiting the wide-spread use of V8s was the difficulty and complexity of casting one-piece blocks. Henry Ford did more to solve this issue than anyone else, with the release of his flathead V8. We just had to wait for overhead valves to be added to the recipe, and then the real fun began!

The Dawning of an Era (1955 – 1963)

As exciting as the past couple of years were, things were about to take off. The fire was going to turn into a blaze. This era, 1955 through 1963, was distinctly different from the preceding post-war era, as well as different from the muscle car era that followed, extending from 1964 through 1974.

1955 saw the landmark Chevy small block introduced, in its 265cid form. In ‘57 it would grow to 283cid, and 1hp/in3 as an optional Corvette engine. It would have dual 4bbl induction, as well as fuel injection. Compression ratios would soon climb past 10:1. By the end if this era, the 327 fuelie would make 360hp, with an 11.25:1 compression ratio!

This wasn’t the only worthwhile engine news, though. Not by far. Chevy also had their big-block 348 and 409cid V8s. Pontiac would introduce their 317, which would grow to 347cid, then 370cid, then become the famous 389.

Things weren’t quite as exciting at Buick and Olds, with the 401 and 394, respectively. It’s not that they made substantially less power than the Pontiac 389, but they clearly hadn’t found their stride yet. The Chrysler companies didn’t take a backseat to anyone. The 392 hemispherical head V8 would approach 400hp, before the “hemi-head movement” lost steam and they were replaced by wedge head engines.

The wonderful, long-lived 383 would be introduced, the 413 would exceed 400hp, and the wild 426 Max Wedge would hit 425hp.

Ford’s 352 would go on to make more than 350hp, and the 390 would break the 400hp mark. The 406 and 427 would follow, taking things to the 425hp mark.

Engine Excitement

This was an exciting time in the American automotive field. Swift change became the norm. The previous ceiling of 200hp would be passed in ’54, and just a couple of years later would see every manufacturer offering multiple models and engines well exceeding this. 1957 and ’58 would see the 300hp level handily passed by as top power levels reached for 400 hp. The decade started with top power levels of about 150hp and ended with several different offerings at or above 400hp! Had this rate continued, the muscle car wars of the ‘60’s would have seen 1,000hp engines!

The 1950’s brought us noteworthy vehicles like the Corvette and the Thunderbird. There was an interesting interplay between the two vehicles, and both would see great success for decades to come. To a significant degree, the Corvette owes its existence to the Thunderbird. Early Corvette sales were disappointing, and the model was actively being considered for cancellation. Then, along came the ’55 Thunderbird. Its sales success showed Chevrolet that there was a market for a two-seat roadster, and if Ford could do it, so could they with the Corvette. They just needed some V8 power and a bit more time. Of course, by the time the Corvette really took off, the Thunderbird had changed into a four-passenger vehicle.

To many Thunderbird lovers today, the ’55 – ’57 models were it; all other years were a distant second place. However, that’s not necessarily how the buying public perceived them at the time. The four-passenger models were real marketing successes. Apparently, people wanted the sportiness, but the limitation of only being able to accommodate one additional person was too much of an obstacle for significant numbers of potential buyers.

Pre-Muscle Car Era Engine Metrics

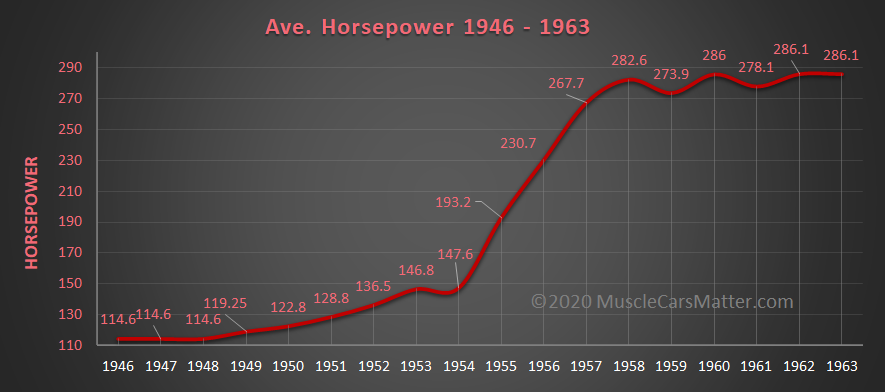

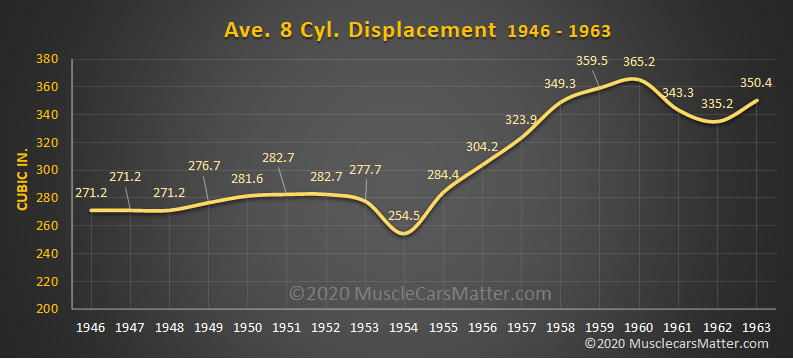

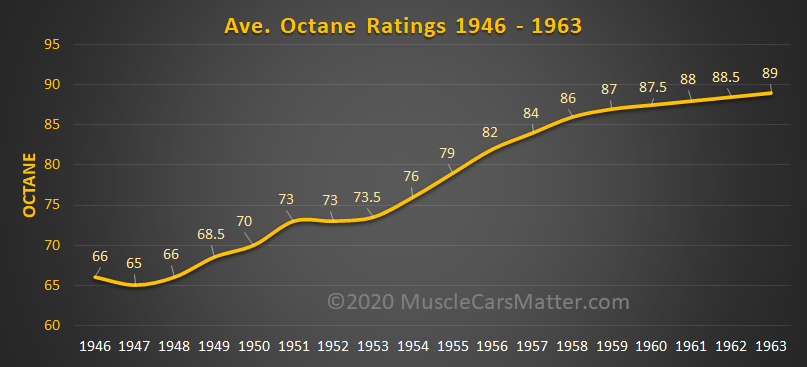

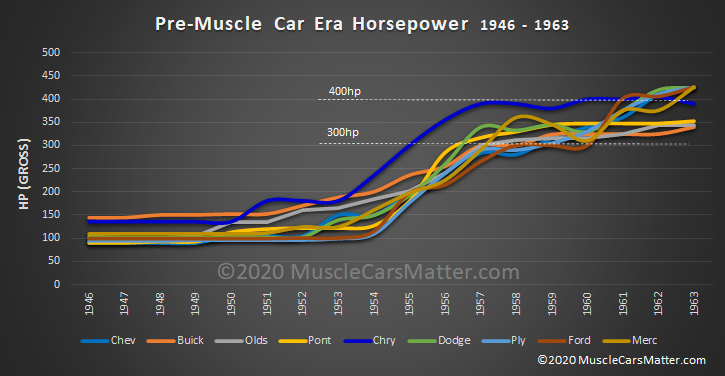

From an engine perspective, the following graphs should give you a pretty complete picture of the ’46 – ’63 era.

The graphs are, in order:

- Average Engine Age

- Average Horsepower

- Average Compression Ratio

- Average 8 Cylinder Displacement

- Average Horsepower per Cubic Inch

- Average Octane

- Average Gasoline Prices

There are a couple of things to keep in mind. For the first several years, ’46 through ’54, both sixes and eights are included. For the graph of Displacement, is just V8 engines.

These graphs don’t take engine production numbers into account. This was intentional. For a simple example, consider the following: A manufacturer made 100,000 200hp engines and just 1,000 400hp engines in a given year. The average horsepower would be the average of 200 and 400, which is 300, even though the overwhelming majority of engines were 200hp. We feel that the manner chosen better reflects the true nature of the era, indicating more accurately what was available.

Average Engine Age

From the Engine Age graph, it’s easy to see that there were no new engines in the first few years. Then, the decline in age was steady until about 1954, when everyone introduced new engines. Many of these were one-year-only versions, which were bored or stroked the next year. Automakers were scrambling to get their feet under themselves. Modifying engine designs each year wasn’t a position they wanted to be in.

Of course, it wasn’t going to be this way forever, as the average age rose to a still extremely low 2+ years in the early ’60’s.

Average Horsepower

Oh, horsepower! 1954 to 1958 was a freakin’ rocket ride! Average power went up by over 130hp in that short period. Again, there was a predictable leveling off after that. By this time, there were a multitude of engines at or above 400hp.

Average Compression Ratio

The general shape of the Average Compression Ratio graph is remarkably like that of the Horsepower graph. The availability of higher-octane gas was key to operating an engine at the 10:1 and above ratios that were seen for the higher output engines during the late ‘50’s and early ‘60’s.

Average 8 Cylinder Displacement

V8 engine displacement reached a peak in 1960, then declined. There weren’t necessarily fewer large engines as much as there were increased numbers of small V8s. Chevrolet was known for their small (block) V8 engines, the 265, 283 and 327. Buick had the wonderful little aluminum 215, which Olds shared the general design of. The Chrysler corp. had the sweet little 318, and Ford had small V8s coming out of their butts! 221, 272, 292, 312, 332, 221, 260, and 289. Add to that Mercury’s 255 and 256. I never could figure out what Ford was thinking.

Average Horsepower per Cubic Inch

The Hp/in3 graph is rather interesting. It shows the same rapid rise starting about 1953, reaches a peak in ’57, then declines slightly and takes six years to reach a new peak in 1963. There are a couple of reasons for this, one of which was the U.S. recession in 1958 and a resulting increased interest in fuel economy. Many engines that would otherwise have been 4bbl-fed were now fueled by 2bbl carburetors, with a resulting drop in horsepower. This was especially true of the “luxury” car segment.

Average Octane Ratings

The Average Octane graph will give you an idea of the improvement in post-war gasoline quality. Had this not been the case, the overall compression ratios could not have increased in the manner they did.

U.S. automakers and oil companies both had vested interests in making gasoline affordable. Toward that end, additives were investigated that could increase octane ratings without resorting to costly additional refining. That additive was TEL, or tetraethyl lead. What was conveniently ignored was that this substance is a deadly poison!

Gasoline Prices

The ’46 to ’63 gas prices (blue) show the gradual increase you might have expected. What’s not so intuitive are the prices relative to 2019 dollars. This is mostly due to the changing rates of inflation during the period. Due to the differences in scales (0 – $0.35, $2.30 – $3.00), a 10% change in the Price (blue) is going to look less significant in a 10% change in the Price 2019$ (orange). In ’46 – ’47, an increase of a couple of cents is actually a significant drop in the adjusted (2019) price, while in ’59 – ’63, the price remaining constant during strong inflation results in a plunge in the adjusted price.

1946 through 1963 Automotive Market

It’s interesting to note the peaks and valleys of the Sales graph, and how the different companies tend to be in sync with one another. Peak sales years, as shown, were 1947, 1950, 1953, 1955, 1957, 1960 and 1962-63.

Regarding the Market Share graph, the huge ‘49 – ’50 peak in Ford sales, after poor performance in ’47 and ’48, requires some explanation.

While most makes saw ’47 sales similar to ’46, Ford (the company) was the exception to this. Hence, the Ford and Mercury market share dropped dramatically. They then experienced tremendous ’49 sales, as did the GM companies.

Also, Ford shut down production of the ’48 models in the middle of the 1948 calendar year to set up for the all-new ‘49’s. Additionally, these models were introduced two or three months early, which further reduced the ’48 numbers, while increasing the ’49.

Market Share Graph

The Market Share graph displays similar trends to the Sales graph, but removes the peaks and valleys caused by market sags and surges. It’s clear that Ford and Chevrolet had something of a see-saw battle for the number one position, with Chevrolet dominating. The red dash-dot “Ford+Chevy” line is the total of these two companies.

The graph above shows a few interesting things. First and foremost, Chevrolet and Ford controlled roughly one half of the total market. Plymouth and Buick each had shares approaching or exceeding 10%, with Pontiac and Oldsmobile also having significant shares at times. The rest were mostly lost in the noise.

Ford and Chevrolet ended up with a greater share of the overall market at the end of this period than they had at the beginning. No other automakers showed significant gains, and both Chrysler and Plymouth experienced period-long declines.

Note that from 1957 on, the Ford+Chevy market share exceeds 50% of the total market. The overall era was, more than anything, the “Ford, Chevrolet, and everyone else Story”.

Total Auto Sales

The Sales Percentage Change by Year graph is interesting in that it shows the cyclic nature of the automotive business incredibly well. You have to be careful, though, and pay attention to the 0% line. Take 1950 and 1951 as examples. 1950 was a peak year, but the change in ’51 was close to 0%, or ‘no change’. 1951 wasn’t a bad year at all; far from it! 1952 is another matter. The Korean War caused a substantial drop in the automotive market, as shown by the 30% – 50% drop everyone experienced.

It might help to do the mental exercise of picturing a fictitious company who experienced 10% growth each and every year. Their graph line would be simply a flat horizontal line at the 10% mark. With 10% growth, they would be growing at a wonderful rate, but this type of graph wouldn’t show it quite as obviously as maybe a sales-by-year graph would, where the line would be tilted upward.

Mercury Strangeness

In looking at more details from the graph, you will see that Mercury was down in ’48, like everyone else, but their 1949 saw a 500% change! Their sales change in 1960 was roughly twice that of anyone else for this year, but the few following years saw lowered performance. Mercury’s yearly sales were lower than most makes, which means that smaller net sales changes will be reflected by higher percentages.

The ’49 peak was a clear indication of this, but the 1960 peak is a bit harder to explain. If you look at the Market Share graph, you’ll see that Mercury actually approached the number three position for 1961! This was their highest market share for this entire era. It was followed by slightly lower sales in ’62 and ’63, and virtually everyone else was anywhere from slightly higher to substantially higher, thus Mercury’s fall back to 8th place.

Mercury’s ’59 sales were about even with their ’58, while most companies were up for ’59. Merc’s ’60 sales were up, when everyone else was coming off of the ’59 peak. The Mercury Percentage Change is out of sync with the rest of the market by one year. If you look at the ’48 to ’50 range, you will see less obvious examples of the same out-of-sync behavior with some of the makes.

The Reason?

I have to think that Mercury’s pairing with Ford comes into play here. Mercury was but a tiny part of Ford, with Ford itself vying for number one each year. If a small percentage of Ford buyers were attracted to Mercury in a given year, this could create huge percentage changes in Mercury’s sales. That might have been a factor in 1949 and 1960. With all of the divisions GM had, this sort of effect would never have been as significant.

The other factor in the 1960 sales percentage change for Mercury was undoubtedly the introduction of their new little Comet. It was introduced in March, yet sold some 117,000 copies, which accounted for 43% of Mercury sales for the year!

Horsepower for the Common Man

Engine offerings played a direct role in these market results and the battles for consumers. As can be seen by the chart below, the competition over horsepower began in earnest in the early ‘50’s and took off in about 1955.

People wanted more power, and not just for the performance-oriented cars. Obviously, the power demand was greater for some types of cars than for others, but the demand existed across the board.

The graph above shows the highest horsepower offerings of each of the automakers. 150hp was about the limit until 1950, which makes perfect sense. For the first handful of years after the war, companies were focusing on many other things, new engines taking a back seat.

The years of 1954 to 1958 were nothing less than a rocket ride! Horsepower more than doubled, with each of the companies taking part, some more than others. It was an exciting time!

Engine Offerings by Company

The following tables, by manufacturer, show the growth in engine size, engine numbers and engine horsepower over this period of time. Within the cells, the numbers “AA/BB” are (Intro or low hp) / (highest hp).

GM Companies

Chevy started this period with their 217cid straight six and didn’t even offer a larger displacement than this until 1950. At least it was an OHV design, but at 90 and 105hp, who really cared?

Chevrolet crossed the 300hp barrier in 1959, but that was with a smallish engine, with less torque than some of the competition.

Buick came into the post-war era with only eight-cylinder engines, which were both overhead valves. They were unique on both counts. The 144hp of their 320 was competitive with anything else.

Oldsmobile went to a V8-only policy, when the 257cid inline 8 was dropped after 1950. This resulted in them mostly having only one large engine at a time.

Pontiac held on to their 239cid inline six through 1954, and added the 194cid four cylinder in 1961. Their V8 went through several short-lived iterations, starting at 287cid and going to 389cid. Of course, the 421 was also a product of this evolution.

This made Pontiac unique in the regard that their first V8 design was really their only V8 design, spanning from 1955 until well into the ’70’s.

Chrysler Companies

For the last half of this era, Chrysler offered at least two V8 engines that weren’t vastly different in displacements. Hemi offerings were from 1951 through 1958, ending with the wonderful 392.

Dodge engine offerings were on par with those of Chrysler, with few exceptions. Plymouth was the lower cost make, and didn’t have quite the high-output engine availability of Dodge.

Both Plymouth and Dodge began the era with lowly valve-in-block inline sixes. Who would have thought that they would end the era with five or so V8 engines as well a couple of sixes? And one of those was the beautiful Slant Six!

Ford Motor Company

Ford had an interesting, somewhat eclectic engine lineup. Inline sixes and small V8 engines abounded. Did they really feel they needed 221cid, 260cid, 289cid and 352cid V8 engines? As well as 144cid, 170cid and 200cid sixes? They had two large engines at a time, if you ignore the one-year overlap of the 406 and the 427. The 427 was expensive to manufacture, being a thin-wall casting, and the 390 was really the workhorse of the company. It would be detuned in ’63 as the hot engines were now the 406 and the 427. It’s hard to believe that Ford had only two engine offerings from ’46 through ’54, then went from three in ’55 to eleven in ’63!

Mercury more or less followed Ford’s lead. They didn’t get the hottest versions of the 390, and the 406 was one year only. As with Ford itself, the 427 was available for selected vehicles. Merc did start the era with a lone engine offering, only to have nine in 1954!

Engines and Engine Configuration Numbers

Notice how the number of engines takes off in about ’57. Also of note is that while the number of unique engines increases incrementally, the numbers of engine configurations jumps markedly and remains high through the end of the era. This reflects not only market competition, but the attempt to tailor an engine more specifically to the buyer’s needs.

The best example of this might be Pontiac and their 389. They had 2bbl and 4bbl versions, both low compression (for regular gas) and 10+:1 for higher performance. Added to this was the top-shelf 3 x 2bbl version for those who wanted maximum fun.

Korean War (1950 – 1953) and Chrome

The Korean war affected the American auto industry, though it was almost nothing compared to World War II. There were shortages of copper and chromium, which meant that chrome plating was at times unavailable, the substitute being a sprayed-on clear protectant. It wasn’t remotely as durable as chrome.

Did you ever wonder about this thing called “chrome”? The element chromium was discovered in the late 18th century and gets its name from the Greek “chroma”, for color. It can make some bright, attractive colors when it’s combined with other elements. Oh—chromium is found as an ore and is the 21st most common element of the earth’s crust.

Simple chrome plating involves electroplating a thin layer of chromium to a metal (or plastic) object. The best process is triple-plating, which deposits a layer of usually copper first, then nickel, and finally chromium. The process of plating with chromium dates back to the early 1920’s.

V8 Market Mayhem

The degree to which buyers embraced V8 engines caught all automakers by surprise. The V8 configuration wasn’t new, as it had existed since the ‘teens. However, it had always been expensive to manufacture V8 engines, due primarily to the difficulty in casting blocks. Early blocks were cast in multiple pieces. The conversion from valve-in-block to overhead valves and the evolution of block casting techniques allowed the benefits of a V8, good affordable power, to be made available to all.

Earlier attempts to provide good, affordable power had led to the development of the inline (L head) eight, which came after the first V8 engines. The problem with a straight eight was the long crankshaft, which severely limited engine rpms. There was also the challenge of feeding fuel and air to a long line of cylinders, as well as the challenge of designing a body around a really long engine. The straight eight was for the guy who wanted power but couldn’t afford a V8.

1946 – 1963 Engine Development by Automaker

When the WW2 ended and US automakers resumed production of cars, it was a monumental undertaking to get to the point of having vehicles roll off the assembly lines. Production was not shifted from war materiel to cars overnight. Given this, it’s entirely predictable that for the first few years, there should be no substantive advancements in design or mechanics.

New designs were introduced by most automakers in 1949, with the engine advancements not far behind. The floodgate was about to be opened, and Americans would begin to learn what it was like to drive a modern V8 powered car that didn’t necessarily have to cost a fortune. Horsepower for the common man!

Here we’ll look at the highlights and milestones of engine development of this era.

- Chrysler Corp

- Hemispherical Head Engines

- Polyspherical Head Engines

- 241

- 259

- 277

- 301

- 303

- 331

- 356

- Chrysler RB-Series

- 383

- 413

- 426

- Chrysler B-Series

- 350

- 361

- Chevrolet

- Small block

- 265

- 283

- 327

- W-Series

- 348

- 409

- Small block

- Buick

- 215

- Nailhead

- 264

- 322

- 364

- 401

- 425

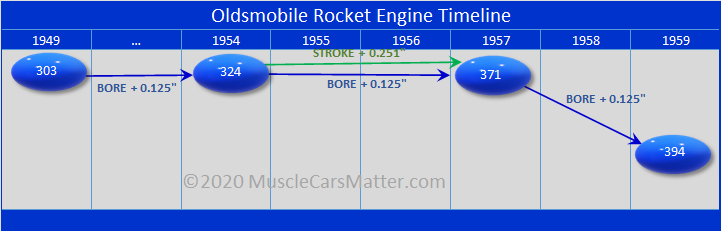

- Oldsmobile

- 215

- 304

- 324

- 371

- 394

- Pontiac

- 287

- 317

- 347

- 370

- 389

- 421

- Ford Motor Company

- Lincoln Y-Block

- Ford-Mercury-Edsel Y-Block

- 239

- 256

- 272

- 292

- 312

- Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln

- 383

- 410

- 430

- Ford FE Series

- 332

- 352

- 360/361

- 390

- 406

- 427

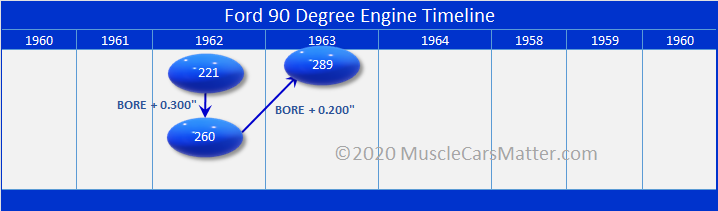

- Ford 90 Degree Series

- 221

- 260

- 289

Chrysler Corp Engines

Chrysler Corp. Early Hemispherical and Polyspherical Head Engines

The story of the first series of Chrysler company hemi-head engines is absolutely fascinating, and has all of the elements of a good novel.

Hemispherical-shaped combustion chambers were not new, even in the mid-to-late 1930’s, when the Chrysler research began. They were not at all widely used. Chrysler engineers had been tasked with testing a multitude of different engine and head configurations and selecting one that would become the standard on which future Chrysler company engines would be based. This research started before WWII and continued, in some form, through the war years.

Chrysler Corp. Displacement-O-Rama

GM companies and Ford never seemed to have this level of ‘WTC*’. While there was a bit of engine sharing in GM and a bit more in Ford motor Company, they didn’t begin to approach the level of the Chrysler companies. Was it a Dodge engine, a Chrysler engine or a Plymouth engine. Who the hell knows, and to an extent, who cares!

Another source of confusion was, for example, whether an engine was a Chrysler hemispherical head engine of 331cid or whether it was a polyspherical head engine of the same displacement. Then, Dodge had both 325cid and 326cid engines, and Plymouth had its 301 and 303cid engines. It was like trying to watch a basketball game when you didn’t know the teams and didn’t have a program. Believe me when I say that this stuff even confuses hardcore Mopar guys!

*WTC What the Crap. A gentler, kinder, more mature equivalent of the more familiar ‘WTF’.

331cid hemispherical head V8

In 1951 Chrysler fired one of the first shots in the horsepower war, making good use of their pre- and wartime experience. Their first overhead valve V8 was the 331 hemi (small ‘h’), with 180hp on tap. This would grow to 300hp by 1955 with 2x4bbl induction. This family of engines was given the name “Fire Power”. Connecting rod length was 6.625″. The crankshaft was forged steel, the connecting rods were forged and the pistons were made of cast aluminum alloy. The camshaft was hydraulic. The later high-output versions had forged pistons, solid lifter cams and 1x4bbl or 2x4bbl carburetion. Chrysler only.

354cid hemispherical head V8

1956 would see the 331 bored by 0.125” to become the 354, with up to 280hp from the start. This engine would be in use for three years, its last year being 1958. Connecting rod length was 6.625″. In 1957 and 1958 there would also be 354cid poly-head engines for the lower two series. Chrysler only.

392cid hemispherical head V8

The very next year, 1957, the definitive early hemi engine would arrive, the 392. It’s bore and stroke were both increases over the 354. This engine would make 380hp and 450 lb.-ft of torque. Connecting rod length was 6.950″. Chrysler only.

Chrysler had the lead in the introduction of these new engines, and Dodge, Plymouth and DeSoto would all have to wait a bit to introduce theirs. In addition, Chrysler had the engine that was unquestionably at the top of the heap, in the 392.

Chrysler, Dodge and DeSoto would each have their own, entirely unique, hemispherical-head engine designs. This was before the era of (much) corporate sharing of engines and technology. As an example of this, in a few years, Chevy would have their own 350, Pontiac theirs, Buick theirs and Oldsmobile theirs, all entirely different engines that had the same approximate displacement.

These were all hemispherical head engines, with the exception of the 1955 – ’56 331 that had polyspherical heads.

Hemi heads are large and wide, and require additional machining, relative to wedge heads. Valvetrain hardware is more substantial and pistons are of a more complex design. The pistons must be domed to achieve the desired compression ratio, which results in more complex pistons. Stud mounted rockers, like Chevy’s, won’t work.

Hemispherical combustion chambers were cool looking, weren’t they? The extra machining required added to the cost of production of these engines.

Hemi engines, whether small ‘h’ or large ‘H’, were some of the most attractive engines made. Heck, I’d even go as far as to say they were downright sexy!

Dodge Engine Offerings

Dodge had to wait until 1953 for their new engine, the 241. It was a good bit smaller than the 331 that Chrysler had brought to market in 1951. Its 140hp wasn’t going to impress many, either. In ’55 the 241 would be bored by 0.1875” to become the 270. This engine produced up to 189hp. Finally, in 1956, by merit of a 0.5625” increase in bore, the 315 would appear. With a 9.25:1 compression ratio and two 4bbl Carters, this engine would make 295hp. Not too shabby.

241cid Hemispherical Head Engine

As was the norm with hemispherical head engines, the 241 sported a forged steel crankshaft, forged connecting rods, cast pistons and a hydraulic camshaft. This engine was christened ‘Red Ram’. 1953 through 1954.

270cid Hemispherical Head Engine

A 0.1875″ bore of the 241 gave us the 270cid engine in 1955. The name was ‘Super Red Ram’. 1955 only.

270cid Polyspherical Head Engine

This was, naturally, a polyspherical head version of the Super Red Ram. The poly head engine was given the name Red Ram. 1955 through 1956.

315cid Hemispherical and Poly Head Engines

in 1956 the 270cid engine received an addition to the stroke of 0.562in. to make the 315cid engine. It made 260hp with a 4bbl carb and 295hp with 2x4bbl carburetion. Poly head versions were labeled Red Ram and Super Red Ram. 1956 only for both versions.

318cid Polyspherical Head Engines

This was the premier poly-head engine, primarily due to its incredible longevity, first as a Chrysler ‘A’ series engine then starting in 1967 as a Chrysler ‘LA’-series engine. 1960 through 1966 as a Chrysler ‘A’ series.

325cid Hemispherical and Poly Head Engines

The 325 made its appearance in 1957 and consisted of both poly and hemispherical head engines. Red Ram and Super Red Ram were the polyspherical-heads and the D500 was the hemi-head engine. Top output was 310hp, courtesy of 2x4bbl carburetion. 1957 through 1958 for poly engines; 1957 only for hemispherical head.

326cid Polyspherical Head Engine

This appeared as a 1959 Dodge engine and displaced 325.25 cubic inches. It was referred to as 326cid to avoid confusion with the 325cid engine. It shared the stroke of the 318 and had hydraulic lifters. Interestingly, this was a one year only engine, 1959.

Both the 315 and the 325 were under-square, with strokes larger than their bores. This was unusual, and the exact opposite of many engines a decade earlier. The industry would gravitate to bore/stroke values that were moderately over-square. The color coding in the Bore/Stroke column groups engines by common stroke values.